One Last Issue, Nothing Else to Write [Green Arrow 2023]

(Contains spoilers...)

The Serenity

“Expectations are the enemy of an artist” says Ron Perlman, ex-Hellboy, while giving an interview recently. “Nothing felt like it was going to be something special (…) wired for failure”. Although at that point of the podcast, Ron is talking about FX’s Sons of Anarchy (one of my all-time shows), my impression is that this kind of mental juggling act is inevitable, at least to some extent, in any form of creative endeavor.

In the case of writer Chris Condon and draftman Montos standout Green Arrow run, their conundrum lay in establishing a distance between Oliver Queen and Joshua Williamson’s immediately preceding tenure: one that, although cosmic in scale and responsible for restoring the Arrow family back to its status quo, felt a bit of a lackluster when viewed against the seasons he spent with The Flash and Superman—or at least that’s what cruised my mind at the time. For me, his entire tenancy felt more like a skeletal structure for the Absolute Power event that was developing by that time, and in which Oliver played a pivotal role as the hero turned villain and then back a hero again.

As a matter of opinion, the entirety of the All-In era has felt like a superlative, bombastic, and in some instances, hypocoristic publishing revamp of DC’s superhero stories. Not that there’s anything negative about it, but it’s rather the fact that having a few to no books that feel consequential, weighty, what makes waiting for new issues each month less daunting—Tom King’s Wonder Woman and Ram V’s The New Gods are but a few of the selected exceptions that come to mind: more gritty, gnarly, and pressing books.

Prima facie, the fourteen printed issues by Condon, Montos, and company seem to fit into this latter group. While not exactly The Sopranos (mostly for having a green-clad protagonist a la Errol Flynn), Green Arrow (2023) still manages to tackle some major real-life problems (as in big pharma or expropriations) with statements and an atmosphere not so distant from those in movies like Se7en, Sicario, or Heat. First with The Freshwater Killer arc, and now with The Crimson Archer storyline, these more gravitational stories recover both the aesthetics and the pathos of some of the best books from the Bronze and the Dark Ages of comics, namely Denys Cowan’s The Question, Starlin/Wrighton’s Batman, and, naturally, Mike Grell’s Green Arrow.

From Montos’ texture work and sfumato-esque style, to the unsolvable nature of the themes pitched up by Condon, a big chunk of the attractiveness of this series is reminiscent not only of DC’s books all through the eighties, but also the end of Modernity as a whole and the atmosphere of disenchantment, disillusionment, and pessimism that characterized the peak of Post-Modernity and the intrigue of how to resolve the colapse of the world.

The Courage

Nevertheless, despite this taxonomic familiarity, Condon and Montos decided to land a subversive gimmick in the way the outcomes for these stories were presented throughout their run. While the books of the Dark Age were overrun with streets blighted by serial killers, prostitutes, and drug dealers, with ethical extremes and even more extreme decisions (thus making them seem urgent), Green Arrow feels less dramatic and more… domestic.

The further we move into the twenty-first century, the more problems like drug dealing and the violence associated with it seem impossible to resolve; the same is true for claims regarding hidden defects in properties, state corruption, and the fusion between government and market. Therefore, there is a brilliance in Condon turning his attention to other, more “mundane” affairs that we can, indeed, sort out: strained relationships between fathers and sons, drug rehabilitation, rebuilding social trust, or simply listening to those who are suffering.

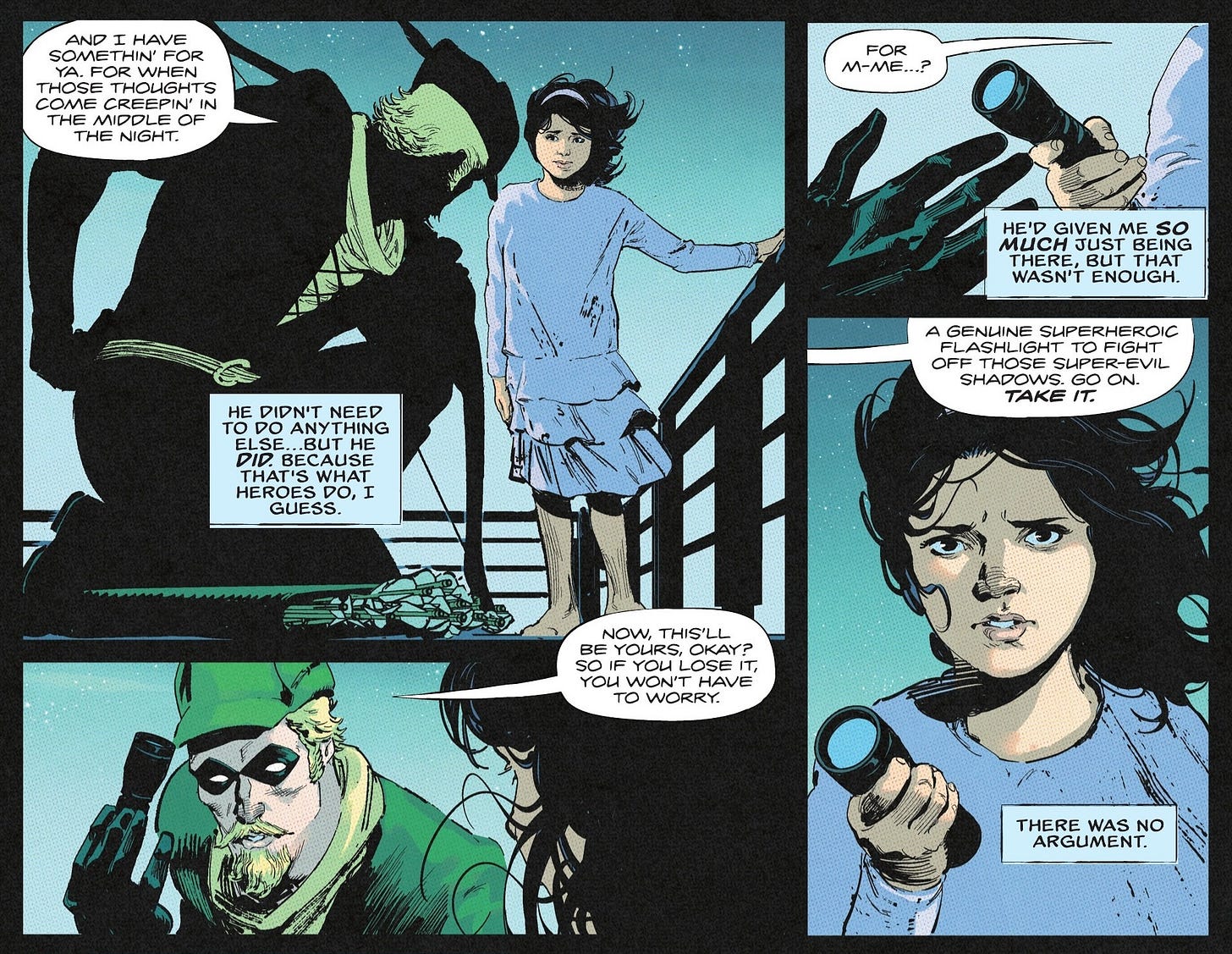

In this sense, Oliver Queen is not only the ideal man for the job, but his last issue is a primary example of how beautifully crafted these kinds of tales are. In Green Arrow #31, there’s no looming armageddon in the background, threatening to throw us back into the Stone Age, nor are there any insurmountable issues about the nature of morals. No. Instead, this is what we have: a little girl who has lost her mother and is left with a father whose mind has been bent by anger and sorrow, and someone who, by chance, stumbles upon the little girl and listens to her woes. And, ask me or not, that’s exactly how you bid farewell to a superhero—or at least to this superhero.

The kind of drawbacks Oliver has to face during Condon and Montos “swan song” feel, curiously, more pressing than any nihilistic, ultra-violent, and “serious” scenario coming out from 80’s comics, and the way they are addressed is, even when cut off in reach (or maybe because of that), closer to each one of us. Green Arrow isn’t the kind of character that can do the impossible (and neither should he), but rather the kind that does his best, and right here he is, in fact, at his very best: reassuring a frightened girl by telling her that she can feel a million things inside, contradicting one with the other, and still be right and still be brave.

The truth is, thinking about those global and paradigmatic shifts isn’t something that suits Oliver Queen. His approach is to “listen to the other side,” to stay with them, sharing emotions, experiences, and advice. It’s all about those gestures that, as this run, stay with you not because of their scale or grit, but because of their significance, which grows over time, and when feeling all alone. Something quite common, but never easy, and that, precisely due to their everyday nature, you weren’t expecting them to strike as they do. “Y’know, I don’t just punch the bad guys. Sometimes I even listen (…) You can talk to me”.

The Wisdom

It’s a tragedy (of some kind, I think…) having to lose this book before its collaborators could become the next Snyder and Capullo. Still, perhaps, that was for the best: Condon and Montos’ Green Arrow will endure in its readers as an oddity; a book with a penchant for the evocative instead of the expository, for contemplation instead of the action in an editorial environment reigned by the Absolute line of books.

And so forth, Perlman’s comment on expectations comes full circle: with the goodbye issue of a run that didn’t have too much interest in recovering its predecessor status quo or in integrating into the larger DC sphere, and whose last pages are neither a coda to its last saga nor a tease for what future awaits the character. It’s just people talking, and somehow, it still makes it for one of the best titles DC has released in years, and for the best one-shot of 2025. Let’s hope for Condon and Montos to, one day, find their way back to Green Arrow (and Buddy Bedouin, too! One hell of a letterer), but that’s just me expecting.